- Home

- C. L. Moore

Jirel of Joiry Page 13

Jirel of Joiry Read online

Page 13

She looked up, trying to remember, seeing the dark slopes tilting over her head. High above, on a ledge of outcropping stone, she could see gray creepers dropping down the rocky sides, the tips of tall trees waving. She stared upward toward the ledge whose face she could not see, wondering what lay beyond the vine-festooned edges. And:

In a thin, dark fog the mountainside melted to her gaze. Through it, looming darkly and more darkly as the fog thinned, a level plateau edged with vines and thick with heavy trees came into being before her. She stood at the very edge of it, the dizzy drop of the mountain falling sheer behind her. By no path that feet can tread could she have come to this forested plateau.

One glance she cast backward and down from her airy vantage above the dark land of Romne. It spread out below her in a wide horizon-circle of black rock and black waving tree-tops and colorless hills, clear in the clear, dark air of Romne. Nowhere was anything but rock and hills and trees, clear and distinct out to the horizon in the color-swallowing darkness of the air. No sight of man’s occupancy anywhere broke the somberness of its landscape. The great black hall where the image burned might never have existed save in dreams. A prison land it was, narrowly bound by the tight circle of the sky.

Something insistent and inexplicable tugged at her attention then, breaking off abruptly that scanning of the land below. Not understanding why, she answered the compulsion to turn. And when she had turned she stiffened into rigidity, one hand halting in a little futile reach after the knife that no longer swung at her side; for among the trees a figure was approaching.

It was a woman—or could it be? White as leprosy against the blackness of the trees, with a whiteness that no shadows touched, so that she seemed like some creature out of another world reflecting in dazzling pallor upon the background of the dark, she paced slowly forward. She was thin—deathly thin, and wrapped in a white robe like a winding-sheet. The black hair lay upon her shoulders as snakes might lie.

But it was her face that caught Jirel’s eyes and sent a chill of sheer terror down her back. It was the face of Death itself, a skull across which the white, white flesh was tightly drawn. And yet it was not without a certain stark beauty of its own, the beauty of bone so finely formed that even in its death’s-head nakedness it was lovely.

There was no color upon that face anywhere. White-lipped, eyes shadowed, the creature approached with a leisured swaying of the long robe, a leisured swinging of the long black hair lying in snake-strands across the thin white shoulders. And the nearer the—the woman?—came the more queerly apart from the land about her she seemed. Bone-white, untouched by any shadow save in the sockets of her eyes, she was shockingly detached from even the darkness of the air. Not all of Romne’s dim, color-veiling atmosphere could mask the staring whiteness of her, almost blinding in its unshadowed purity.

As she came nearer, Jirel sought instinctively for the eyes that should be fixed upon her from those murky hollows in the scarcely fleshed skull. If they were there, she could not see them. An obscurity clouded the dim sockets where alone shadows clung, so that the face was abstract and sightless—not blind, but more as if the woman’s thoughts were far away and intent upon something so absorbing that her surroundings held nothing for the hidden eyes to dwell on.

She paused a few paces from the waiting Jirel and stood quietly, not moving. Jirel had the feeling that from behind those shadowy hollows where the darkness clung like cobwebs a close and critical gaze was analyzing her, from red head to velvet-hidden toes. At last the bloodless lips of the creature parted and from them a voice as cool and hollow as a tomb fell upon Jirel’s ears in queer, reverberating echoes, as if the woman spoke from far away in deep caverns underground, coming in echo upon echo out of the depths of unseen vaults, though the air was clear and empty about her. Just as her shadowless whiteness gave the illusion of a reflection from some other world, so the voice seemed also to come from echoing distances. Its hollowness said slowly,

“So here is the mate Pav chose. A red woman, eh? Red as his own flame. What are you doing here, bride, so far from your bridegroom’s arms?”

“Seeking a weapon to slay him with!” said Jirel hotly. “I am not a woman to be taken against her will, and Pav is no choice of mine.”

Again she felt that hidden scrutiny from the pits of the veiled eyes. When the cool voice spoke it held a note of incredulity that sounded clearly even in the hollowness of its echo from the deeps of invisible tombs.

“Are you mad? Do you not know what Pav is? You actually seek to destroy him?”

“Either him or myself,” said Jirel angrily. “I know only that I shall never yield to him, whatever he may be.”

“And you came—here. Why? How did you know? How did you dare?” The voice faded and echoes whispered down vaults and caverns of unseen depth ghostily, “—did you dare—did you dare—you dare…”

“Dare what?” demanded Jirel uneasily. “I came here because—because when I gazed upon the mountains, suddenly the world dissolved around me and I was—was here.”

This time she was quite sure that a long, deep scrutiny swept her from head to feet, boring into her eyes as if it would read her very thoughts, though the cloudy pits that hid the woman’s eyes revealed nothing. When her voice sounded again it held a queer mingling of relief and amusement and stark incredulity as it reverberated out of its hollow, underground places.

“Is this ignorance or guile, woman? Can it be that you do not understand even the secret of the land of Romne, or why, when you gazed at the mountains, you found yourself here? Surely even you must not have imagined Romne to be—as it seems. Can you possibly have come here unarmed and alone, to my very mountain—to my very grove—to my very face? You say you seek destruction?” The cool voice murmured into laughter that echoed softly from unseen walls and caverns in diminishing sounds, so that when the woman spoke again it was to the echoes of her own fading mirth. “How well you have found your way! Here is death for you—here at my hands! For you must have known that I shall surely kill you!”

Jirel’s heart leaped thickly under her velvet gown. Death she had sought, but not death at the hands of such a thing as this. She hesitated for words, but curiosity was stronger even than her sudden jerk of reflexive terror, and after a moment she contrived to ask, in a voice of rigid steadiness,

“Why?”

Again the long, deep scrutiny from eyeless sockets. Under it Jirel shuddered, somehow not daring to take her gaze from that leprously white, skull-shaped face, though the sight of it sent little shivers of revulsion along her nerves. Then the bloodless lips parted again and the cool, hollow voice fell echoing on her ears,

“I can scarcely believe that you do not know. Surely Pav must be wise enough in the ways of women—even such as I—to know what happens when rivals meet. No, Pav shall not see his bride again, and the white witch will be queen once more. Are you ready for death, Jirel of Joiry?”

The last words hung hollowly upon the dark air, echoing and re-echoing from invisible vaults. Slowly the arms of the corpse-creature lifted, trailing the white robe in great pale wings, and the hair stirred upon her shoulders like living things. It seemed to Jirel that a light was beginning to glimmer through the shadows that clung like cobwebs to file skull-face’s sockets, and somehow she knew chokingly that she could not bear to gaze upon what was dawning there if she must throw herself backward off the cliff to escape it. In a voice that strangled with terror she cried,

“Wait!”

The pale-winged arms hesitated in their lifting; the light which was dawning behind the shadowed eye-sockets for a moment ceased to brighten through the veiling. Jirel plunged on desperately,

“There is no need to slay me. I would very gladly go if I knew the way out.”

“No,” the cold voice echoed from reverberant distances. “There would be the peril of you always, existing and waiting. No, you must die or my sovereignty is at an end.”

“Is it sovereignty or Pav’s love that I

peril, then?” demanded Jirel, the words tumbling over one another in her breathless eagerness lest unknown magic silence her before she could finish.

The corpse-witch laughed a cold little echo of sheer scorn.

“There is no such thing as love,” she said, “—for such as I.”

“Then,” said Jirel quickly, a feverish hope beginning to rise behind her terror, “then let me be the one to slay. Let me slay Pav as I set out to do, and leave this land kingless, for your rule alone.”

For a dreadful moment the half-lifted arms of the figure that faced her so terribly hesitated in midair; the light behind the shadows of her eyes flickered. Then slowly the winged arms fell, the eyes dimmed into cloud-filled hollows again. Blind-faced, impersonal, the skull turned toward Jirel. And curiously, she had the idea that calculation and malice and a dawning idea that spelled danger for her were forming behind that expressionless mask of white-fleshed bone. She could feel tensity and peril in the air—a subtler danger than the frank threat of killing. Yet when the white witch spoke there was nothing threatening in her words. The hollow voice sounded as coolly from its echoing caverns as if it had not a moment before been threatening death.

“There is only one way in which Pav can be destroyed,” she said slowly. “It is a way I dare not attempt, nor would any not already under the shadow of death. I think not even Pav knows of it. If you—” The hollow tones hesitated for the briefest instant, and Jirel felt, like the breath of a cold wind past her face, the certainty that there was a deeper danger here, in this unspoken offer, than even in the witch’s scarcely stayed death-magic. The cool voice went on, with a tingle of malice in its echoing.

“If you dare risk this way of clearing my path to the throne of Romne, you may go free.”

Jirel hesitated, so strong had been that breath of warning to the danger-accustomed keenness of her senses. It was not a genuine offer—not a true path of escape. She was sure of that, though she could not put her finger on the flaw she sensed so strongly. But she knew she had no choice.

“I accept, whatever it is,” she said, “my only hope of winning back to my own land again. What is this thing you speak of?”

“The—the flame,” said the witch half hesitantly, and again Jirel felt a sidelong scrutiny from the cobwebbed sockets, almost as if the woman scarcely expected to be believed. “The flame that crowns Pav’s image. If it can be quenched, Pav—dies.” And queerly she laughed as she said it, a cool little ripple of scornful amusement. It was somehow like a blow in the face, and Jirel felt the blood rising to her cheeks as if in answer to a tangible slap. For she knew that the scorn was directed at herself, though she could not guess why.

“But how?” she asked, striving to keep bewilderment out of her voice.

“With flame,” said the white witch quickly. “Only with flame can that flame be quenched. I think Pav must at least once have made use of those little blue fires that flicker through the air about your body. Do you know them?”

Jirel nodded mutely.

“They are the manifestations of your own strength, called up by him. I can explain it no more clearly to you than that. You must have felt a momentary exhaustion as they moved. But because they are essentially a part of your own human violence, here in this land of Romne, which is stranger and more alien than you know, they have the ability to quench Pav’s flame. You will not understand that now. But when it happens, you will know why. I cannot tell you.

“You must trick Pav into calling forth the blue fire of your own strength, for only he can do that. And then you must concentrate all your forces upon the flame that burns around the image. Once it is in existence, you can control the blue fire, send it out to the image. You must do this. Will you? Will you?”

The tall figure of the witch leaned forward eagerly, her white skull-face thrusting nearer in an urgency that not even the veiled, impersonal eye-sockets could keep from showing. And though she had imparted the information that the flame held Pav’s secret life in a voice of hollow reverberant mockery, as if the statement were a contemptuous lie, she told of its quenching with an intensity of purpose that proclaimed it unmistakable truth. “Will you?” she demanded again in a voice that shook a little with nameless violence.

Jirel stared at the white-fleshed skull in growing disquiet. There was a danger here that she could feel almost tangibly. And somehow it centered upon this thing which the corpse-witch was trying to force her into promising. Somehow she was increasingly sure of that. And rebellion suddenly flamed within her. If she must die, then let her do it now, meeting death face to face and not in some obscurity of cat’s-paw witchcraft in the attempt to destroy Pav. She would not promise.

“No,” she heard her own voice saying in sudden violence. “No, I will not!”

Across the skull-white face of the witch convulsive fury swept. It was the rage of thwarted malice, not the disappointment of a plotter. The hollow voice choked behind grinning lips, but she lifted her arms like great pale wings again, and a glare of hell-fire leaped into being among the shadows that clung like cobwebs to her eye-sockets. For a moment she stood towering, white and terrible, above the earthwoman, in a tableau against the black woods of unshadowed bone-whiteness, dazzling in the dark air of Romne, terrible beyond words in the power of her gathering magic.

Then Jirel, rigid with horror at the light brightening so ominously among the shadows of these eyeless sockets, saw terror sweep suddenly across the convulsed face, quenching the anger in a cold tide of deadly fear.

“Pav!” gasped the chill voice hollowly. “Pav comes!”

Jirel swung round toward the far horizon, seeking what had struck such fear into the leprously white skull-face, and with a little gasp of reprieve saw the black figure of her abductor enormous on the distant skyline. Through the clear dark air she could see him plainly, even to the sneering arrogance upon his bearded face, and a flicker of hot rebellion went through her. Even in the knowledge of his black and terrible power, the human insolence of him struck flame from the flint of her resolution, and she began to burn with a deep-seated anger again which not even his terror could quench, not even her amazement at the incredible size of him.

For he strode among the tree-tops like a colossus, gigantic, heaven-shouldering, swinging in league-long strides across the dark land spread out panorama-like under that high ledge where the two women stood. He was nearing in great distance-devouring steps, and it seemed to Jirel that he diminished in stature as the space between them lessened. Now the treetops were creaming like black surf about his thighs. She saw anger on his face, and she heard a little gasp behind her. She whirled in quick terror, for surely now the witch would slay her with no more delay, before Pav could come near enough to prevent.

But when she turned she saw that the pale corpse-creature had forgotten her in the frantic effort to save herself. And she was working a magic that for an instant wiped out from Jirel’s wondering mind even her own peril, even the miraculous oncoming of Pav. She had poised on her toes, and now in a swirl of shroud-like robes and snaky hair she began to spin. At first she revolved laboriously, but in a few moments the jerky whirling began to smooth out and quicken and she was revolving without effort, as if she utilized a force outside Jirel’s understanding, as if some invisible whirlwind spun her faster and faster in its vortex, until she was a blur of shining, unshadowed whiteness wrapped in the dark snakes of her hair—until she was nothing but a pale mist against the forest darkness—until she had vanished utterly.

Then, as Jirel stared in dumb bewilderment, a little chill wind that somehow seemed to blow from immeasurably far distances, from cool, hollow, underground places, brushed her cheek briefly, without ruffling a single red curl. It was not a tangible wind. And from empty air a hand that was bone-hard dealt her a stinging blow in the face. An incredibly tiny, thin, far-away voice sang in her ear as if over gulfs of measureless vastness,

“That for watching my spell, red woman! And if you do not keep our bargain, you sha

ll feel the weight of my magic. Remember!”

Then in a great gush of wind and a trample of booted feet Pav was on the ledge beside her, and no more than life-size now, tall, black, magnificent as before, radiant with arrogance and power. He stared hotly, with fathomless blackness in his eyes, at the place where the mist that was the witch had faded. Then he laughed contemptuously.

“She is safe enough—there,” he said. “Let her stay. You should not have come here, Jirel of Joiry.”

“I didn’t come,” she said in sudden, childish indignation against everything that had so mystified her, against his insolent voice and the arrogance and power of him, against the necessity for owing to him her rescue from the witch’s magic. “I didn’t come. The—the mountain came! All I did was look at it, and suddenly it was here.”

His deep bull-bellow of laughter brought the blood angrily to her cheeks.

“You must learn that secret of your land of Romne,” he said indulgently. “It is not constructed on the lines of your old world. And only by slow degrees, as you grow stronger in the magic which I shall teach you, can you learn the full measure of Romne’s strangeness. It is enough for you to know now that distances here are measured in different terms from those you know. Space and matter are subordinated to the power of the mind, so that when you desire to reach a place you need only concentrate upon it to bring it into focus about you, succeeding the old landscape in which you stood.

“Later you must see Romne in its true reality, walk through Romne as Romne really is. Later, when you are my queen.”

The old hot anger choked up in Jirel’s throat. She was not so afraid of him now, for a weapon was in her hands which even he did not suspect. She knew his vulnerability. She cried defiantly,

“Never, then! I’d kill you first.”

His scornful laughter broke into her threat.

“You could not do that,” he told her, deep-voiced: “I have said before that there is no way. Do you think I could be mistaken about that?”

The Complete Jirel of Joiry

The Complete Jirel of Joiry Quest of the Starstone

Quest of the Starstone The Tree of Life

The Tree of Life Judgment Night

Judgment Night The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987

The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987 Northwest of Earth

Northwest of Earth No Boundaries

No Boundaries The Best of C. L. Moore

The Best of C. L. Moore Doomsday Morning M

Doomsday Morning M Shambleau and Others M

Shambleau and Others M Jirel of Joiry

Jirel of Joiry Judgment Night M

Judgment Night M Northwest Smith

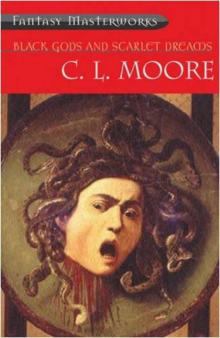

Northwest Smith Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams

Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams