- Home

- C. L. Moore

Doomsday Morning M Page 19

Doomsday Morning M Read online

Page 19

But a sort of mechanical life was returning to me. From a long way off I seemed to remember dimly what this scene was about. I could even perceive how far off base we had distorted it, and creakily my mind began to wonder how we could pull it back. I was moving stiffly now, but at least I was moving. I picked uphe sense of the last line I’d heard and croaked something in answer. Probably it made no sense, but at least I’d spoken on my own.

There was a horrible familiarity about all this. I’d had the curtain rung down on me before, when I was incompetent to go on. When I’d been too drunk or too despairing to care. But never before had I gone as blank as this, or in just this stunned, frozen way. I felt as if all aliveness had been drained out of me and nothing remained but some mechanical puppet that could move and speak only when somebody turned the crank.

Somehow, and how none of us ever knew, we got the scene moving. Everybody was ad-libbing wildly. On any normal stage the curtain would have come down by now. But here there was no curtain. Guthrie could have cut the lights, but he was too inexperienced to realize quite what was happening. I could, remotely and indifferently, imagine his fury as yet again I ruined the continuity of the play, but there wasn’t much he could do to me—yet.

Toward the end of the scene something resembling life came faintly back into me and I was able to pick up the latent meaning of the lines and carry my end of it after a fashion. My tongue was stiff and my mouth dry, but somehow the scene did move toward a close not entirely alien to the close we’d rehearsed so often. I felt the tension relax a little out of the cast around me.

When I went off for my three-minute break toward the middle of the play Polly, waiting under the grandstand, grabbed me by the shoulders and sniffed my breath. Then she shook her head in a baffled way and whispered, “Here,” holding out a pint bottle. I grabbed it like a drowning man and what felt like half of the contents slid down my throat before the impact really hit me. I had a seizure of agonizingly muffled coughing. Then I thought the whole drink was going to come back up again. Then the warmth began to spread and I leaned back and let myself go limp, feeling the relaxation of the alcohol take hold. It occurred to me dimly that this was the first drink I’d had in—how many days?—and I hadn’t even missed it until now.

Polly wrenched the bottle out of my hand when I lifted it again. “Go easy! You’re on again in a minute. How do you feel?”

I wiped my mouth with the back of an ice-cold hand. “Give me my next line.”

She whispered it. I tried it over a couple of times, feeling the scene come slowly and stiffly back into my mind. But it was a dead scene as I thought of it now. Peopled by the dead, enacted by clockwork men and women in a dead clockwork world. …

And I thought of the last time this hollowness had come over me, when I took Cressy, warm and responsive into my arms in the moonlight and the strong, soft wind—was it only last night? Just twenty-four hours ago. And I’d swung insanely since then between upbeats of manic exhilaration and downbeats of dead despair.

I thought, Am I out of my mind? What’s wrong with me? What’s happening?

Polly said, “There’s your warning. Can you go on?”

I straightened my back and breathed deep of dead night air. “Oh yes,” I said, hearing my voice hollow and flat in my own head, “I can go on.”

And I did.

Somehow while I’d been off stage the cast had wrenched the scene around toward something near normality, and when I stepped in on cue I was able to pick up the line Polly had fed me with a minimum of changing to lit the situation. And painfully, creakily, we labored through to the end. It was a dogged business. I had to be prompted a lot. Time after time I went blank again. And when I wasn’t blank, still I was dead. But somehow we made it.

The audience was kinder than we deserved. They sat with us to the bitter end. They coughed and squirmed a lot, they whispered in the flatter scenes, nobody laughed at the jokes. But at least they didn’t walk out. Probably very few of them had ever seen the living theater before, and they must have gone home with the impression that it’s a dreary business compared with television and the films. But at least they didn’t mob us.

The stands emptied. The lights went off. I sat down under the grandstand and took the pint bottle away from Polly. She surrendered it in silence. She and the rest of the cast stood there looking down at me, too bewildered to talk very much. This was outside their experience. Or mine. Everybody goes blank on stage sometimes. We all knew that. We all knew the usual things to say and do about it afterward. But this blankness that had hit me was too abnormal for anybody to cope with. They were still muttering uneasily to each other and watching me finish the pint when Guthrie came around the end of the stands and walked over to me.

I didn’t look up. I knew his feet and legs and I saw no point in taking the trouble to see what his face looked like. I didn’t hear him speak, but the other feet and legs within sight began to move away as if he’d given silent orders. The whiskey was humming inside my head just above the ears in an obscurely comforting way. I sucked down the last of it, grateful to the man who invented oblivion. Over the upended bottle I looked at Guthrie.

He wasn’t red with anger any more. He looked quite pale, and the sad eyes were stony. He’d stopped being a cracker-barrel philosopher and he looked like the Comus man he was, resolute and ruthless. In a quiet voice that didn’t carry any farther than he meant it to, he said:

“You’ve fouled up every job since you joined us, Rohan. I’ve had enough. I don’t know what kind of a deal you have with Mr. Nye about other things, but I know you’re through with this troupe. I’ve already sent for a replacement. You can pack up and leave right now. You’re out of the Swann Players, Rohan.”

It almost seemed to me, in the haze of whiskey that hummed above my ears, that he was speaking not in words at all. He was speaking in letters of fire which I didn’t have to read because I didn’t want to. Because it hurt too much to understand what he was really saying. …

I think I was in and out of more than one bar that night. seem to remember a lot of yelling and singing. I can’t be sure because my little buzzing room had rebuilt itself around me and through those walls nothing unpleasant can ever penetrate. I balanced it delicately around me like a big, humming bubble. I wasn’t quite sure what went on outside any more. Sometimes it seemed maybe I was back in that Cropper bus jolting along the road between the Ohio fields. Other times I could almost think I was back with the troupe, also jolting along, but this time in the caravan trucks, a tight little working group talking over the play, heading for—where was it?—Carson City and a new performance.

Except that I was washed up for good as a performer. If tonight had proved anything it had proved that.

And I couldn’t really imagine even in my buzzing magic room that I was with the troupe again. I remembered too vividly standing in the road with my travel pack in my hand, watching them diminish in the moonlight. They had said good-by in subdued voices, not quite meeting my eyes. And the little world they were part of went spinning away down the dark road, leaving a hollow inside me too cold for liquor to warm and too vast for liquor to fill.

But I tried. I tried hard.

CHAPTER XXII

THE SKY WAS transparently blue far up straight over my face. Treetops leaned together up there, swaying with a slow, dizzying motion. There seemed to be pine needles under me, but I had no idea where I was, or even who. A flicker of warning at the back of my mind suggested it would be better not to remember who. No good could come of that.

I sat up slowly. The motion made my head open and close once like a thunderclap. I held it together with both hands, fighting nausea. A hangover? Then I must have been drunk. … Step by step I retraced the immediate past, working backward from the hangover. Then the mellow sunlight went black around me as I remembered.

Everything was over. The dazzling future I’d thought I had secure had slipped like quicksilver through my fingers and I was right back w

here I’d started. Not an actor after all. Nothing. I remembered the dead, frozen hour on stage. I saw Guthrie again, standing over me, looking down, pronouncing the words of excommunication. And everything had ended.

And I had dreamed a strange dream again. …

I looked around the little clearing in the woods where I seemed to have spent the night. The night and a good part of the day, if the westering sunlight that slanted through the trees was anything to go by. I was trying to remember the dream.

Miranda. What was it? The theater had been in it—how? Something ridiculous—the traveling theater was a ring of bombs ticking toward explosion, set up on end like a circular palisade and inside it Miranda, going through some scene of infinite importance to me, but quite soundlessly, her lovely mouth opening and closing without a word while letters of fire shimmered over her and her corn-silk hair blew softly about her face.

Wait. Corn-silk? Miranda’s hair was dark. It was Cressy who had the corn-silk curls. Something had been wrong in the dream. Miranda and Cressy blended into one? I didn’t like it. Miranda and Cressy had nothing in common at all. Miranda was love and loyalty and brilliance and beauty. Miranda was all of me that had been worth having. Miranda was the rock I had stood on and the fire that had lighted me and made me what I was. Without her the world was a quagmire and the light a darkness. And I nothing.

In the dream rage and frustration had bubbled up in me. Miranda was saying something I had to know, had to, but the letters of fire wouldn’t stand still to be read, and some kind of roaring like a hurricane had troubled my dream, and I remembered dimly doubling my fist hard and hitting someone, some enemy who stood between me and all I wanted. I hated him. I felt my fist sink into him and I heard him grunt.

But then, in the midst of the hurricane roar, I had opened my eyes and found I was hitting the carpet of pine needles over and over, hard, angry blows. The roar diminished into distance and my hand hurt from beating my enemy the earth. And I had sunk again into a confusion of dreams, because waking was even worse than sleep.

I heard the roaring rise again as I sat here trying to remember. It rushed toward me in crescendo, shivered the leaves around me, and swept by fast into the distance. A truck on the highway. So I had somehow last night stumbled out of town and found this hollow among the pines beside the road the troupe had taken going away. Polly and Roy, Cressy and Guthrie, the Henkens diminishing down a long highway with all their plans and problems, leaving me alone with mine.

My head ached. I rubbed my bristling cheek and wondered what came next. A faint hopefulness flickered in me and I asked myself why, after all, everything had to be over. Guthrie had fired me, yes. But who had the final word? Nye was the man I worked for, not Guthrie. Would Nye care if I froze up in the play? So maybe the job of actor wasn’t for me any more. I was here for more than acting. I was on the track of the Anti-Com itself and Guthrie had no authority to stop me. All I had to do was get in touch with Nye, finish up my job of finding the Anti-Com, and——

And what? And earn back the theater I couldn’t use any more? Step back into the old life as an actor who couldn’t act? What place would there be for Rohan in a world he couldn’t function in? No, I’d been right all along, from a long time ago, from the hour of Miranda’s death. Maybe that’s what the letters of fire had said in last night’s dream. Without Miranda I was nothing. I’d always known it. With her I was more than myself, strong and powerful and alive. Alone I was less than a single person. So that one good performance when I’d turned the world underfoot had been one last flash before darkness, and the bad performance was the true reflection of myself.

So what good was Nye to me now? What could he give me that I cared for? Miranda back again?

Still, I had to do something. I couldn’t sit here forever. I got up stiffly and looked at the sinking sun. A few hours from now the Swann Players would be setting up their grandstands in Carson City. Where would I be? Did it matter? Ofuthown accord the memory of the dream came back urgently into my mind. The theater was a ring of bombs minute by minute ticking toward the blowoff. And it did matter that I should be there. Why, I didn’t know. But an anxiety trembled in me for something I couldn’t name. Something furiously raging to be heard in my mind, and an inward force that said “No, no, be quiet, I don’t hear you.”

Moving stiffly, I toiled up the slope toward the sound of passing traffic.

The heavy truck rumbled to a halt in the twilight. “Here we are,” the driver said. “Carson City.” He slanted a look at me. “You all right, bud?”

I got my chin off my chest and forced a grin. I’d been bad company all the way from Douglass. There was too much on my mind. I said, “Sure, I’m fine,” and got painfully out of the cab. He watched me, taking in my scratches and bruises, the rips is my clothing. He shook his head at me. I said, “Well, thanks for the lift.”

He hesitated, looking me over. Then he reached into one of the dash compartments and tossed a package at me. “Here, catch,” he said. It was a ration pack, one of the food boxes drivers carry on long hauls. I wondered if I looked that hungry, but I caught it gratefully. There was no knowing how long I’d have to make my money last from now on. The driver was still looking at me as he pulled away, and just before the motor downed out all other sound, I think he spoke. I think what he said was, “I used to like your pictures, Mr. Rohan.” But I’ll never know now.

I got some coffee at a stand near the highway. It helped a little. Carson City isn’t very big. There’s a park near the center of town, with a pool in the middle and big trees deep with summer leaves that have a rich, rolling motion when the wind blows. I found a bench and ate some of the food in the ration pack, not wanting any and hot liking it much, but knowing I’d feel better when it was down. I did.

By then darkness had fallen, and now all I had to do was follow the crowd. Crosswords pulled very well in Carson City. This was the town which Nye had told me was important. This was the place where he wanted a big audience with all the rebels in it he could get. Looking up at the bleachers from outside, hearing the first familiar lines sounding in familiar voices, I wondered in how many other towns in California tonight Crossroads was being played. And whether there was something really special about Carson City. And what.

All the voices from inside the magic ring were familiar except one. The one that spoke my lines. I felt like a ghost.

I waited until I was sure Guthrie would be busy doing whatever it was he did do in the sound truck and the cast was all on stage. Then I slipped between the girders and the wall and climbed up the stands to a seat high up, near the top. Almost every seat had been taken. I fell over a few feet and dropped into a vacant spot.

Sitting there looking down at the lighted stage, I felt very strange. I was part of the play and not part of it. I couldn’t quite believe I was sitting here as an onlooker, because I knew the play so was And the oddest titling of all was watching the man who played my part. The man pretending to be Howard Rohan in the role in which I’d hit such heights and such depths. He handled it well. Well enough. He was about my size and coloring, and he played with a clean, sharp accuracy and no life at all. For the first time Crossroads was going to be seen in this theater exactly as it was written.

The cast was nervous. The man in my part was just a little off in his timing because he’d rehearsed with a different group. More than once he wasn’t quite where he should have been when somebody turned to speak to him. Once I noticed Polly’s face draw tight and a little bleak at a moment like that, and it seemed to me that she was seeing me, Rohan, a ghostly presence in that vacant spot exactly as I was seeing myself there. I thought with some wonder, watching her face, Maybe they miss me after all.

My hangover had receded a long way by now. I felt almost willing to cope with being alive again. I looked at the audience and wondered what they made of this exotic thing, a live play in the street of Carson City. They were laughing responsively in all the right spots, the kind of audience the pe

ople on the stage love and appreciate.

I found, rather to my surprise, that I was thinking about the Anti-Com.

I noticed that Cressy’s pale gold hair needed retouching along the part, seen from this high up. I noticed that Roy had used too much eye shadow, so his deep-set eyes looked small and haggard. I made mental notes to speak to them both, and brought myself up with a shock, remembering that I and the Swann Players had nothing to do with each other any more.

I saw a familiar head down there a couple of rows ahead of me and leaned forward to look with surprise. I had seen her in San Andreas bending over the lie box I was hooked to. I had seen her in the mountain valley above the rebels’ distribution center, with the ‘hopper exploding before her and the Comus forces closing in. Dr. Elaine Thomas. She sat composedly on the bench below me wearing a yellow dress with a blue sweater thrown across her shoulders. The black hair was drawn tight in its usual coronet of braids, and the slightly tilted eyes were intent upon the stage. I looked quickly at her hand and saw a ring upon it with the big blue stone intact.

Cressy in the strong lights below us swung her bright pink skirts in a half circle and put out both hands to the man who was playing my part. They stood there laughing at each other, radiant in the brilliant light. I felt a twinge of curious jealousy. Cressy was putting more intimacy into the part than Susan Jones had to put. She was Cressy Kellogg, too, the little opportunist, playing up with all the sparkle that was in her to the new man in the cast. Because, who knows, there might be something in it for Cressy Kellogg.

She tipped her head sidewise and the corn-silk curls swung out. A shudder of anxiety without any cause I could name went through me coldly. She was Miranda suddenly, the Miranda of my dream moving in the circle of ticking bombs. For some reason my eyes moved to Elaine Thomas there on the bench below me smiling and watching. And it seemed to me death was in the air around us, chilly and smelling of dust.

The Complete Jirel of Joiry

The Complete Jirel of Joiry Quest of the Starstone

Quest of the Starstone The Tree of Life

The Tree of Life Judgment Night

Judgment Night The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987

The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987 Northwest of Earth

Northwest of Earth No Boundaries

No Boundaries The Best of C. L. Moore

The Best of C. L. Moore Doomsday Morning M

Doomsday Morning M Shambleau and Others M

Shambleau and Others M Jirel of Joiry

Jirel of Joiry Judgment Night M

Judgment Night M Northwest Smith

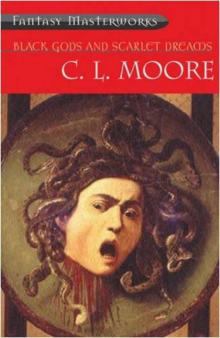

Northwest Smith Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams

Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams