- Home

- C. L. Moore

Doomsday Morning M Page 5

Doomsday Morning M Read online

Page 5

And somebody had seen fit to thumbtack to the thick bark at the edge of the slab a little notice that said, “Charlie Starr licked Comus at San Diego—1993.” I stood there looking at it and wondering. This was something new. Back in ‘93 when Miranda and I were in full swing, what had we heard about a man named Starr and trouble in San Diego? Nothing at all. Suddenly I remembered that chalked star on the truck trailer with ‘93 scrawled inside it.

I shrugged. It was just barely possible, I told myself with some irony, that things had happened in San Diego in ‘93 that Comus hadn’t cared to publicize. Whatever it was, I felt excitement waking in me uncertainly. Even that long ago, then, trouble had been brewing out here. A little scuttling sound in the needles startled me and I looked down to see a chipmunk dart along the path, twitching his skimpy tail convulsively. I put San Diego neatly away in the back of my mind and followed the chipmunk down the path. Off among the trees somebody was laughing.

At the edge of the trees I stopped. This would make a good stage-set for some still unwritten play. I thought, Call it Howard Rohan, His Fall and Rise. Rohan stands at the edge of the clearing and gazes into his own future.

The firelight was the first thing you saw, flickering pale in the gloom and the quiet. It burned in a low stone stove with an iron plate for a cover. Beside the stove were two plank tables spotted with grease. Somebody a long time ago had made benches by splitting big redwood logs in half lengthwise and nailing one of the halves up vertically for a back rest. Beyond the benches three trucks stood, with SWANN COMPANY PLAYERS very ornate in luminous pink paint along the sides.

The trucks were good-sized but they looked small under the towering columns of the trees. The whole encampment looked small. There were six people in the camp, and they looked small too. They were talking and laughing a little among themselves, but even their voices sounded small, hushed and dwarfed by the enormous silence of the redwoods.

I stood there quietly, looking them over. I knew I was scared. I could feel the disquiet shiver in me because of all the times in the past that I’d tried a comeback and failed. But here it was, the raw material of my last chance, waiting to be shaped.

Six people. The six Swann Players the man in my dream had told me about—if that was what he told me. Maybe it’s a far cry from collecting swans to joining the Swann Players. Maybe it isn’t. I looked from face to face wondering which of them I’d come on the strength of a dream to see. But it had been only a dream, after all. The letters of fire circled unreadably before me for an instant and then faded. Whatever that dream had tried to say to me would have to stay unsaid so far as I could tell. I drew a deep breath, ran my palm over my head with the old gesture, and braced myself. This wouldn’t be easy. But if anybody got hurt this time it wasn’t going to be Howard Rohan.

Six faces rose to look at me as I walked toward them over the dust and the pine needles. All expression faded from every one of them. They had been laughing a moment ago, but now nobody even smiled. They looked at me coldly and waited.

“Hello,” I said. There was a stony silence.

I said again, “Hello.” Then I added, “Oh, for God’s sake. The name is Howard Rohan. Weren’t you expecting me?”

Nobody spoke.

A man in a checkered shirt sitting on one of the benches laid down the screwdriver he’d been using to probe the innards of a flat sleep-teach box. The wooden handle of it thumped on the bench. He reached under his collar, scratched, gave me a quick, furtive grin, and went dead-pan again. I glanced around the circle. Nobody else flickered an eye. It was the freeze-out.

“I see you’ve heard of me,” I said.

Still silence. The whole clearing pulsed with it. Somewhere off stage the river made its brawling noises. A bird chirped, a pine cone fell with a soft, decisive thump. Nobody moved. They were a closed group, close-knit, shutting me out. For just an instant the only thing I felt was an intense and terrible loneliness. In the instant it seemed to me I smelled not woodsmoke and pine, but the exciting, musty, indescribable smell of the theater backstage, sweat and dust and old wood, make-up, tobacco smoke. I saw not this group alone, but every cast I’d ever worked with, and somewhere on the fringe of them, just out of sight, I had the strange impression that Miranda stood in the wings, one foot poised to step forward and join me.

The old feeling came over me again for a moment and I was glad to have it come. These aren’t real people, they’re clockwork figures among cardboard trees and nobody on earth is alive since Miranda died. So if they close up into a unit and shut me out, it doesn’t matter. They’re only clockwork. And like clockwork, I looked them over appraisingly.

My friend in the checkered shirt was now lighting his pipe. He didn’t look like an actor, but he did remind me of something intensely familiar that I couldn’t quite place. He was pushing sixty-five, I thought, and he looked broody, as if with any encouragement he might turn into a cracker-barrel philosopher.

At one of the grease-stained plank tables two other men sat over a spread of dog-eared cards. One of them was youngish, say thirty-five, which made him about five years younger than I am. He had a heavy, good-looking face and tan curls cut short. His eyes were too deep-set, and when he scowled, as he was scowling now, they seemed to sink back into their sockets until he looked like an ill-natured ape. The other man was soft and plump, with a respectable white thatch and a red nose.

Three women and a coffeepot made up the rest of the group. The old woman sat away from the rest, on a blanket spread out on the pine needles, giving most of her attention to a little box about a foot square, out of which a very small yammering rose, like distant mice staging an opera. The woman had white curls, wrinkles, and the mild, mad look of an aging Ophelia. The box had a glass front and was full of little brightly colored figures gesturing and singing in tiny voices to the music of some unseen orchestra that must have fitted into a matchbox. The strange feeling of smallness and magic persisted even after I’d recognized the thing as a cheap playbox for canned opera. I could see its cord tailing off and plugged into a socket set in the nearest tree, which had in itself a touch of the fantastic.

Nothing here in the clearing seemed quite real. I kept thinking if I turned my head fast enough I might catch a glimpse of Miranda moving always just beyond the periphery of vision. She was so much a part of the theater and my own past that my mind couldn’t quite accept the idea of one without the other. That, at least, was how I rationalized it, until I got a clear look at the youngest of the three women in the troupe.

The middle-aged one-obscured her. She was in the very act of pouring coffee into a cup held by the youngest when I stepped into the clearing, and the two of them paused in arrested motion, both faces turned to stare. The middle-aged woman had a plump, pretty, hourglass figure and a haggard face. Her blue eyes bulged a little and she had orered hair combed slickly back to a knot high up on her head. It was not red like hair, but red like blood. Or Comus. The kind of color you get only after a plastic dip job, because only a plastic coating will take color like that. Under the coating the hair was probably mostly gray. Whoever she was, she looked tired and a little embittered, as if somehow she had never really expected age would catch up with her. I didn’t care. I had my own problems.

Then she moved a little and the girl behind her looked me fully in the face, and for a moment time stood still.

Only for a moment. This was no miracle. The Swann Players were a second-rate troupe and you don’t find Mirandas among the second-rate. But she looked so like Miranda that for one wild, ridiculous, joyful moment my mind against all reason said to me, “She’s come back—she’s here—it was all a nightmare and I’ve waked up again. …” Maybe in heaven, if there is a heaven, that moment will really come when we see the dead again face to face and for an instant believe and can’t believe. But only then. Not now. Never here and now.

She was no Miranda. But she had a dim reflection of the luster that had made Miranda radiant, made her name so perfectly

right for her that you really did think, oh, wonderful! when you first saw that lovely face. Something in this girl’s poise, the way her body moved and her head sat on her pretty neck and the way she tilted it, was like Miranda. She had proportions like hers. And she wore her hair in the same halo of big loose curls that Miranda invented and every girl in the country copied three years ago. Miranda’s hair was a very rich chestnut, and this girl’s was bleached to a corn-silk pallor, but the likeness at first glance was too strong not to notice.

I felt like turning around and walking away.

I looked them all over, impassively, face by face. My mind said, “Second-rate, second-rate.” And I thought, This isn’t for me. I can’t face it. I won’t try. The state’s in revolt, the troupe’s scraped up from the barrel bottom, the play’s untried. The audiences will be yokels. It isn’t worth the effort. Because I was washed up and I knew it. And I couldn’t stand the reminder of Miranda, and I knew how painful the living world can be. Better go back to being clockwork and live in a dead world. All I wanted now was a drink.

In front of them all, knowing what they knew about me, I set down my bag, got my bottle out, and drank one long, deep, satisfying draught. It burned my throat and started the little bright fire going inside me that I’d missed without quite knowing what was wrong. I was perfectly clear about what I meant to do. A man can take just so much.

I put the bottle back in the bag.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said distinctly, “I see you’ve all heard of me. You don’t like what you’ve heard. That’s all right with me. I’ve never heard of you. I don’t like this setup. There’s a lot I’d rather be doing than coaching a broken-down carnival in a country on the edge of a revolution. But we haven’t got much choice.” I picked up my bag. “I’ll be back with you in ten minutes,” Id. “I want everybody ready to start work when I get here. All right. That’s all.”

I turned and walked briskly off the way I’d come. Strangely, I felt a twinge of regret as I did it. The troupe in the clearing with the twilight gathering and the fire crackling shared their own kind of magic room, I thought. The tall, still trees, the smell of coffee, the small distant singing defined their circle, shutting me out. But the part of my life that touched the theater world was over and gone. And Miranda with it. And I wanted nothing to do with it anymore.

(It wasn’t entirely true. Miranda might be gone, but she was always with me. Everywhere. Waking and sleeping, wherever I went I never went alone.)

Out of sight of the camp I left the path and cut through ferny thickets toward the highway. The pine needles bounced so springily underfoot I had a false illusion of youth as I walked quietly away from the campfire and my own past. It was getting dark under the trees, but the road glimmered ahead of me and I scrambled toward it, slipping now and then on the needles. I remembered a slope north of the truck stop where the drivers would have to go slow. I could hitch a ride, or steal one. It didn’t much matter. All I wanted was to hit the Canadian border before Comus caught up with me.

I came out on the highway and began trudging north. It was very still here. The wind in the sequoias made a lonesome sound, but a good one. Now and then a bird made faint chipping noises in the foliage, and the river ran over rapids somewhere down to the left. The camp and the troupe were part of a world that never existed. My own past, my own future. I never wanted to see the girl like Miranda again. I never would. The best I could hope for was to let the beautiful dreamer sleep on.

The road was wide and faintly visible in the last lingering light that still made the sky paler than the earth. The automatic drive lines glowed white in long, singing ribbons, humming their endless song about the power of Comus.

Because of the dimness at first I didn’t see the man in the checkered shirt leaning against a tree at the edge of the highway between me and the road. He just leaned there, quite comfortable, arms crossed, and cradled over his left elbow a little blue pistol with a gold Comus ring around the muzzle. It was my broody friend the philosopher. He grinned at me in the dimness rather sadly. His voice was mild.

“You might have got halfway to Oregon at that,” he said. “But you’d run into Comus sooner or later. Things are still going on just as usual in northern Oregon and all through Washington.”

I swallowed a couple of times and drew a deep breath. I kept my voice as casual as his.

“I thought you weren’t an actor,” I said. It was perfectly simple to place him now. Comus cops have a sort of generic likeness. I’ve never known if it’s acquired or inherent, screened out by the very fact that they qualify for Comus.

“Oh, I earn my way,” he said. “I’m the sound-truck man, among other things.” I noticed that when he hato stop grinning to speak the polite melancholy settled back on his face. The smile never went deep or stayed long. “There’s one of us with every troupe on the road here,” he said. “We keep order and—well, make sure of things. I’m sorry, Mr. Rohan, but you’ll have to go back.”

I looked at the gun and at him. Could I out-talk the man, I wondered, or out-dodge him in the twilight? He was much too old for active duty. They catch Comus cops early, train them hard, and retire them as soon as the reflexes start to slow. Maybe before the thinking processes really begin. I wondered why this one had been called back. Nye must really be scraping the bottom of the barrel. But the melancholy eyes above the gold-ringed muzzle were very steady. I could imagine the polite regret with which he’d pull the trigger. Meeting my gaze, he motioned with the gun. “You first, Mr. Rohan,” he said.

I shrugged. “What’s your name?”

“Guthrie. Tom Guthrie.”

“All right, Guthrie. I won’t play games. You’re too old to wear a uniform but I think you may still be faster than I am. Shall we go?”

He gestured again. “You first.” Then his voice dropped slightly. “Mr. Nye tells me he had a talk with you.” He sounded as if Ted were just around the next tree. “It would be better if the rest of the troupe didn’t know any more about you or me than they have to.”

“Then put that gun away,” I said. “I know when I’m licked. I’ll stay put until I figure a better way out than walking off.”

“Mr. Rohan. Wait. Look at me.”

I looked. The towering silence was like a solid wall around us.

“I’m getting old, Mr. Rohan,” Guthrie said. “They called a lot of us back because they needed us. I’m too slow for active duty, but I was trained in things a man never forgets, and I can do my job fine. You’re not a very important part of it, but I’m going to keep you here and you aren’t going to outguess me. Do you believe that?”

I waited a moment. Then I said, “Yes, I believe it.”

“Good. Well, now. We’re in dangerous territory. You don’t like it. Maybe I don’t either. But we do our job, both of us. That means you stay reasonably sober. It means whipping the troupe into shape no matter how tough they make it. When orders come in from headquarters we both abide by them. You’re a part of Comus now whether you like it or not. We can work better if the troupe doesn’t know I’m a cop. But we work together, easy or hard.”

I thought it over, feeling the turmoil swirl in my mind. Past failures, hopes and fears about the future. The beautiful dreamer stirring in her sleep. All right, so I had no choice. But we were headed south. The Mexican border is down there. I shrugged.

“Let’s go,” I said.

CHAPTER VI

I WALKED INTO THE firelit clearing and threw my bag down hard on the nearest bench. I was in a murderous mood. I looked with savage contempt around the campsite and then licked my lip, drew a deep breath, and whistled the raucous, two-toned whistle that calls the cast to order. Some directors use a tin whistle. Some yell. I whistle. Loud and peremptory.

Heads came up with a jerk. Everybody stared. The red-haired woman had been opening flat dinner cans at the farther table and setting them out to heat themselves up in a row on the planks. The girl was filling a bucket at a splashing tap, the co

rn-silk curls jumping as she snapped her head around to stare at me. At the nearer table the two men had been figuring something out on a sheet of paper, their heads close together. They looked up, startled. Only the old woman still sitting on her blanket never glanced up from the little singing box.

“All right,” I said in a loud, hectoring voice. “On stage, everybody. Let’s stop playing games.”

They all looked at me. Nobody spoke, but I saw the red-haired woman move a little so she could keep the corner of her eye on the heavy-faced man scowling up at me from his seat at the table. I saw how she kept her face turned so he was always just within the limits of her vision, and I got the feeling she always stood like this, holding him just in sight.

I took another deep breath and felt the shakiness in me deep down along with the anger. This was my raw material. Out of this and the script in my bag I had to build a play. Out of these scrapings from the barrel bottom, plus whatever was left in me. And however little it was, I told myself savagely, it was still worth more than this whole troupe of has-beens would ever know. Has-beens, never-weres. Never-would-bes unless I could somehow take hold of them and force talent into them enough to get the show under way. If I had to do it, I told myself, by God, I’d do it in a way they’d never forget.

“You there!” I called, making my voice firm and loud. “You, at the table, What’s your name?” And I pointed at the youngish man. His brows met over his nose and he set his jaw and glared at me defiantly. I snapped my fingers. “Sound off!”

Nobody stirred except the old woman, who now looked up and blinked mildly, trying to place me. I took three long forward steps, kicking up dust heavily with every footfall. I was rolling the muscles of my shoulders as I went, liking the feel of heavy power locked up inside me, liking the violent eagerness I could feel welling up. I hoped he would fight. I hoped for trouble. I felt suddenly very good, even the anger submerged. Now we’ll fight. This is the easy way.

The Complete Jirel of Joiry

The Complete Jirel of Joiry Quest of the Starstone

Quest of the Starstone The Tree of Life

The Tree of Life Judgment Night

Judgment Night The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987

The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987 Northwest of Earth

Northwest of Earth No Boundaries

No Boundaries The Best of C. L. Moore

The Best of C. L. Moore Doomsday Morning M

Doomsday Morning M Shambleau and Others M

Shambleau and Others M Jirel of Joiry

Jirel of Joiry Judgment Night M

Judgment Night M Northwest Smith

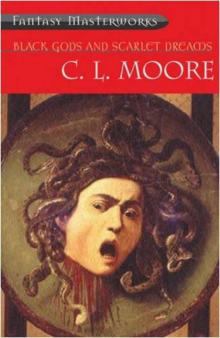

Northwest Smith Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams

Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams