- Home

- C. L. Moore

The Best of C. L. Moore Page 8

The Best of C. L. Moore Read online

Page 8

“I might show you others, Earthman. But it could only drive you mad, in the end—you were very near the brink for a moment just now

—and I have another use for you. . . . I wonder if you begin to understand, now, the purpose of all this?”

The green glow was fading from that dagger-sharp gaze as the Alendar’s eyes stabbed into Smith’s. The Earthman gave his head a little shake to clear away the vestiges of that devouring desire, and took a fresh grip on the butt of his gun. The familiar smoothness of it brought him a measure of reassurance, and with it a reawakening to the peril all around. He knew now that there could be no conceivable mercy for him, to whom the innermost secrets of the Minga had been unaccountably revealed. Death was waiting—strange death, as soon as the Alendar wearied of talking—but if he kept his ears open and his eyes alert it might not—please God—catch him so quickly that he died alone. One sweep of that blade-blue flame was all he asked, now. His eyes, keen and hostile, met the dagger-gaze squarely. The Alendar smiled and said,

“Death in your eyes, Earthman. Nothing in your mind but murder. Can that brain of yours comprehend nothing but battle? Is there no curiosity there? Have you no wonder of why I brought you here? Death awaits you, yes. But a not unpleasant death, and it awaits all, in one form or another. Listen, let me tell you—I have reason for desiring to break through that animal shell of self-defense that seals in your mind. Let me look deeper—if there are depths. Your death will be—useful, and in a way, pleasant. Otherwise—well, the black beasts hunger. And flesh must feed them, as a sweeter drink feeds me. -

Listen.”

Smith’s eyes narrowed. A sweeter drink. - - - Danger, danger—the smell of it in the air—instinctively he felt the peril of opening his mind to the plunging gaze of the Alendar, the force of those compelling eyes beating like strong lights into his brain. . -

“Come,” said the Alendar softly, and moved off soundlessly through the gloom. They followed, Smith painfully alert, the girl walking with lowered, brooding eyes, her mind and soul afar in some wallowing darkness whose shadow showed so hideously beneath her lashes.

The hallway widened to an arch, and abruptly, on the other side, one wall dropped away into infinity and they stood on the dizzy brink of a gallery opening on a black, heaving sea. Smith bit back a startled

oath. One moment before the way had led through low-roofed tunnels deep underground; the next instant they stood on the shore of a vast body of rolling darkness, a tiny wind touching their faces with the breath of unnamable things.

Very far below, the dark waters rolled. Phosphorescence lighted them uncertainly, and he was not even sure it was water that surged there in the dark. A heavy thickness seemed to be inherent in the rollers, like black slime surging.

The Alendar looked out over the fire-tinged waves. He waited for an instant without speaking, and then, far out in the slimy surges, something broke the surface with an oily splash, something mercifully veiled in the dark, then dived again, leaving a wake of spreading rip-pies over the surface.

“Listen,” said the Alendar, without turning his head. “Life is very old. There are older races than man. Mine is one. Life rose out of the black slime of the sea-bottoms and grew toward the light along many diverging lines. Some reached maturity and deep wisdom when man was still swinging through the jungle trees.

“For many centuries, as mankind counts time, the Alendar has dwelt here, breeding beauty. In later years he has sold some of his lesser beauties, perhaps to explain to mankind’s satisfaction what it could never understand were it told the truth. Do you begin to see? My race is very remotely akin to those races which suck blood from man, less remotely to those which drink his life-forces for nourishment. I refine taste even more than that. I drink—beauty. I live on beauty. Yes, literally.

“Beauty is as tangible as blood, in a way. It is a separate, distinct force that inhabits the bodies of men and women. You must have noticed the vacuity that accompanies perfect beauty in so many women

the force so strong that it drives out all other forces and lives vampirishly at the expense of intelligence and goodness and conscience and all else.

“In the beginning, here—for our race was old when this world began, spawned on another planet, and wise and ancient—we woke from slumber in the slime, to feed on the beauty force inherent in mankind even in cave-dwelling days. But it was meager fare, and we studied the race to determine where the greatest prospects lay, then selected specimens for breeding, built this stronghold and settled down to the business of evolving mankind up to its limit of loveliness. In time we weeded out all but the present type. For the race of man we have developed the ultimate type of loveliness. It is interesting to

see what we have accomplished on other worlds, with utterly different races. .

“Well, there you have it. Women, bred as a spawning-ground for the devouring force of beauty on which we live.

“But—the fare grows monotonous, as all food must without change. Vaudir I took because I saw in her a sparkle of something that except in very rare instances has been bred out of the Minga girls. FOr beauty, as I have said, eats up all other qualities but beauty. Yet somehow intelligence and courage survived latently in Vaudir. It decreases her beauty, but the tang of it should be a change from the eternal sameness of the rest. And so I thought until I saw you.

“I realized then how long it had been since I tasted the beauty of man. It is so rare, so different from female beauty, that I had all but forgotten it existed. And you have it, very subtly, in a raw, harsh way....

“I have told you all this to test the quality of that—that harsh beauty in you. Had I been wrong about the deeps of your mind, you would have gone to feed the black beasts, but I see that I was not wrong. Behind your animal shell of self-preservation are depths of that force and strength which nourish the roots of male beauty. I think I shall give you a while to let it grow, under the forcing methods I know, before I—drink. It will be delightful. -

The voice trailed away in a murmurous silence, the pinpoint glitter sought Smith’s eyes. And he tried half-heartedly to avoid it, but his eyes turned involuntarily to the stabbing gaze, and the alertness died out of him, gradually, and the compelling pull of those glittering points in the pits of darkness held him very still.

And as he stared into the diamond glitter he saw its brilliance slowly melt and darken, until the pinpoints of light had changed to pools that dimmed, and he was looking into black evil as elemental and vast as the space between the worlds, a dizzying blankness wherein dwelt unnamable horror . . . deep, deep . . . all about him the darkness was clouding. And thoughts that were not his own seeped into his mind out of that vast, elemental dark . . . crawling, writhing thoughts . . . until he had a glimpse of that dark place where Vaudir’s soul wallowed, and something sucked him down and down into a waking nightmare he could not fight. - .

Then somehow the pull broke for an instant. For just that instant he stood again on the shore of the heaving sea and gripped a gun with nerveless fingers—then the darkness closed about him again, but a different, uneasy dark that had not quite the all-compelling power of that other nightmare—it left him strength enough to fight.

And he fought, a desperate, moveless, soundless struggle in a black sea of horror, while worm-thoughts coiled through his straining mind and the clouds rolled and broke and rolled again about him. Sometimes, in the instants when the pull slackened, he had time to feel a third force struggling here between that black, blind downward suck that dragged at him and his own sick, frantic effort to fight clear, a third force that was weakening the black drag so that he had moments of lucidity when he stood free on the brink of the ocean and felt the sweat roll down his face and was aware of his laboring heart and how gaspingly breath tortured his lungs, and he knew he was fighting with every atom of himself, body and mind and soul, against the intangible blackness sucking him down.

And then he felt the force against him gather itself in a final eff

ort

—he sensed desperation in that effort—and come rolling over him like a tide. Bowled over, blinded and dumb and deaf, drowning in utter blackness, he floundered in the deeps of that nameless hell where thoughts that were alien and slimy squirmed through his brain. Bodiless he was, and unstable, and as he wallowed there in the ooze more hideous than any earthly ooze, because it came from black, inhuman souls and out of ages before man, he became aware that the worm-thoughts a-squirm in his brain were forming slowly into monstrous meanings—knowledge like a formless flow was pouring through his bodiless brain, knowledge so dreadful that consciously he could not comprehend it, though subconsciously every atom of his mind and soul sickened and writhed futilely away. It was flooding over him, drenching him, permeating him through and through with the very essence of dreadfulness—he felt his mind melting away under the solvent power of it, melting and running fluidly into new channels and fresh molds—horrible molds. .

And just at that instant, while madness folded around him and his mind rocked on the verge of annihilation, something snapped, and like a curtain the dark rolled away, and he stood sick and dizzy on the gallery above the black sea. Everything was reeling about him, but they were stable things that shimmered and steadied before his eyes, blessed black rock and tangible surges that had form and body—his feet pressed firmness and his mind shook itself and was clean and his own again.

And then through the haze of weakness that still shrouded him a voice was shrieking wildly, “Kill! . . . kill!” and he saw the Alendar staggering against the rail, all his outlines unaccountably blurred and uncertain, and behind him Vaudir with blazing eyes and face

wrenched hideously into life again, screaming “Kill!” in a voice scarcely human.

Like an independent creature his gun-hand leaped up—he had gripped that gun through everything that happened—and he was dimly aware of the hardness of it kicking back against his hand with the recoil, and of the blue flash flaming from its muzzle. It struck the Alendar’s dark figure full, and there was a hiss and a dazzle. .

Smith closed his eyes tight and opened them again, and stared with a sick incredulity; for unless that struggle had unhinged his brain after all, and the worm-thoughts still dwelt slimily in his mind, tingeing all he saw with unearthly horror—unless this was true, he was looking not at a man just rayed through the lungs, and who should be dropping now in a bleeding, collapsed heap to the floor, but at—at—God, what was it? The dark figure had slumped against the rail, and instead of blood gushing, a hideous, nameless, formless black poured sluggishly forth—a slime like the heaving sea below. The whole dark figure of the man was melting, slumping farther down into the pool of blackness forming at his feet on the stone floor.

Smith gripped his gun and watched in numb incredulity, and the whole body sank slowly down and melted and lost all form— hideously, gruesomely—until where the Alendar had stood a heap of slime lay viscidly on the gallery floor, hideously alive, heaving and rippling and striving to lift itself into a semblance of humanity again. And as he watched, it lost even that form, and the edges melted revoltingly and the mass flattened and slid down into a pool of utter horror, and he became aware that it was pouring slowly through the rails into the sea. He stood watching while the whole rolling, shimmering mound melted and thinned and trickled through the bars, until the floor was clear again, and not even a stain marred the stone.

A painful constriction of his lungs roused him, and he realized he had been holding his breath, scarcely daring to realize. Vaudir had collapsed against the wall, and he saw her knees give limply, and staggered forward on uncertain feet to catch her as she fell.

“Vaudir, Vaudir!” he shook her gently. “Vaudir, what’s happened? Am I dreaming? Are we safe now? Are you—awake again?”

Very slowly her white lids lifted, and the black eyes met his. And he saw shadowily there the knowledge of that wallowing void he had dimly known, the shadow that could never be cleared away. She was steeped and foul with it. And the look of her eyes was such that involuntarily he released her and stepped away. She staggered a little and then regained her balance and regarded him from under bent brows. The level inhumanity of her gaze struck into his soul, and yet he

thought he saw a spark of the girl she had been, dwelling in torture amid the blackness. He knew he was right when she said, in a faraway, toneless voice,

“Awake? . . . No, not ever now, Earthman. I have been down too

deeply into hell . . . he had dealt me a worse torture than be knew,

for there is just enough humanity left within me to realize what I

have become, and to suffer. .

“Yes, he is gone, back into the slime that bred him. I have been a part of him, one with him in the blackness of his soul, and I know. I have spent eons since the blackness came upon me, dwelt for eternities in the dark, rolling seas of his mind, sucking in knowledge .

and as I was one with him, and he now gone, so shall I die; yet I will see you safely out of here if it is in my power, for it was I who dragged you in. If I can remember—if I can find the way. . . .“

She turned uncertainly and staggered a step back along the way they had come. Smith sprang forward and slid his free arm about her, but she shuddered away from the contact.

“No, no—unbearable—the touch of clean human flesh—and it breaks the chord of my remembering. . . . I can not look back into his mind as it was when I dwelt there, and I must, I must. . . .“

She shook him off and reeled on, and he cast one last look at the billowing sea, and then followed. She staggered along the stone floor on stumbling feet, one hand to the wall to support herself, and her voice was whispering gustily, so that he had to follow close to hear, and then almost wished he had not heard,

“—black slime—darkness feeding on light—everything wavers so— slime, slime and a rolling sea—he rose out of it, you know, before civilization began here—he is age-old—there never has been but one Alendar. . . . And somehow—I could not see just how, or remember why

—he rose from the rest, as some of his race on other planets had done, and took the man-form and stocked his breeding-pens. . . .“

They went on up the dark hallway, past curtains hiding incarnate loveliness, and the girl’s stumbling footsteps kept time to her stumbling, half-incoherent words.

“—has lived all these ages here, breeding and devouring beauty— vampire-thirst, a hideous delight in drinking in that beauty-force—I felt it and remembered it when I was one with him—wrapping black layers of primal slime about—quenching human loveliness in ooze, sucking—blind black thirst. . . . And his wisdom was ancient and dreadful and full of power—so he could draw a soul out through the eyes and sink it in hell, and drown it there, as he would have done mine if I had not had, somehow, a difference from the rest. Great

Shar, I wish I had not! I wish I were drowned in it and did not feel in every atom of me the horrible uncleanness of—what I know. But by virtue of that hidden strength I did not surrender wholly, and when he had turned his power to subduing you I was able to struggle, there in the very heart of his mind, making a disturbance that shook him as he fought us both—making it possible to free you long enough for you to destroy the human flesh he was clothed in—so that he lapsed into the ooze again. I do not quite understand why that happened—only that his weakness, with you assailing him from without and me struggling strongly in the very center of his soul was such that he was forced to draw on the power he had built up to maintain himself in the man-form, and weakened it enough so that he collapsed when the man-form was assailed. And he fell back into the slime again—whence he rose—black slime—heaving—oozing. . - .“

Her voice trailed away in murmurs, and she stumbled, all but falling. When she regained her balance she went on ahead of him at a greater distance, as if his very nearness were repugnant to her, and the soft babble of her voice drifted back in broken phrases without meaning.

Presently the air began to

tingle again, and they passed the silver gate and entered that gallery where the air sparkled like champagne. The blue pool lay jewel-clear in its golden setting. Of the girls there was no sign.

When they reached the head of the gallery the girl paused, turning to him a face twisted with the effort at memory.

“Here is the trial,” she said urgently. “If I can remember—” She seized her head in clutching hands, shaking it savagely. “I haven’t the strength, now—can’t—can’t—” the piteous little murmur reached his ears incoherently. Then she straightened resolutely, swaying a little, and faced him, holding out her hands. He clasped them hesitantly, and saw a shiver go through her at the contact, and her face contort painfully, and then a shudder communicated itself through that clasp and he too winced in revolt. He saw her eyes go blank and her face strain in lines of tensity, and a fine dew broke out on her forehead. For a long moment she stood so, her face like death, and strong shudders went over her body and her eyes were blank as the void between the planets.

And as each shudder swept her it went unbroken through the clasping of their hands to him, and they were black waves of dreadfulness, and again he saw the heaving sea and wallowed in the hell he had

fought out of on the gallery, and he knew for the first time what torture she must be enduring who dwelt in the very deeps of that uneasy dark. The pulses came faster, and for moments together he went down into the blind blackness and the slime, and felt the first wriggling of the worm-thoughts tickling the roots of his brain.

And then suddenly a clean darkness closed round them and again everything shifted unaccountably, as if the atoms of the gallery were changing, and when Smith opened his eyes he was standing once more in the dark, slanting corridor with the smell of salt and antiquity heavy in the air.

Vaudir moaned softly beside him, and he turned to see her reeling against the wall and trembling so from head to foot that he looked to

The Complete Jirel of Joiry

The Complete Jirel of Joiry Quest of the Starstone

Quest of the Starstone The Tree of Life

The Tree of Life Judgment Night

Judgment Night The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987

The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987 Northwest of Earth

Northwest of Earth No Boundaries

No Boundaries The Best of C. L. Moore

The Best of C. L. Moore Doomsday Morning M

Doomsday Morning M Shambleau and Others M

Shambleau and Others M Jirel of Joiry

Jirel of Joiry Judgment Night M

Judgment Night M Northwest Smith

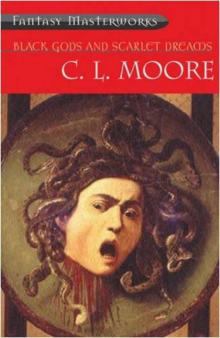

Northwest Smith Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams

Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams