- Home

- C. L. Moore

Jirel of Joiry Page 9

Jirel of Joiry Read online

Page 9

She went forward warily for all that, swinging her sword in cautious arcs before her that she might not run full-tilt into some invisible horror. It was an unpleasant feeling, this groping through blackness, knowing eyes upon her, feeling presences near her, watching. Twice she heard hoarse breathing, and once the splat of great wet feet upon stone, but nothing touched her or tried to bar her passage.

Nevertheless she was shaking with tension and terror when at last she reached the end of the passage. There was no visible sign to tell her that it was ended, but as before, suddenly she sensed that the oppression of those vast weights of earth on all sides had lifted. She was standing at the threshold of some mighty void. The very darkness had a different quality—and at her throat something constricted.

Jirel gripped her sword a little more firmly and felt for the crucifix at her neck—found it—lifted the chain over her head.

Instantly a burst of blinding radiance smote her dark-accustomed eyes more violently than a blow. She stood at a cave mouth, high on the side of a hill, staring out over the most blazing day she had ever seen. Heat and light shimmered in the dazzle: strangely colored light, heat that danced and shook. Day, over a dreadful land.

Jirel cried out inarticulately and clapped a hand over her outraged eyes, groping backward step by step into the sheltering dark of the cave. Night in this land was terrible enough, but day—no, she dared not look upon the strange hell save when darkness veiled it. She remembered that other journey, when she had raced the dawn up the hillside, shuddering, averting her eyes from the terror of her own misshapen shadow forming upon the stones. No, she must wait, how long she could not guess; for though it had been night above ground when she left, here was broad day, and it might be that day in this land was of a different duration from that she knew.

She drew back farther into the cave, until that dreadful day was no more than a blur upon the darkness, and sat down with her back to the rock and the sword across her bare knees, waiting. That blurred light upon the walls had a curious tinge of color such as she had never seen in any earthly daylight. It seemed to her that it shimmered—paled and deepened and brightened again as if the illumination were not steady. It had almost the quality of firelight in its fluctuations.

Several times something seemed to pass across the cave-mouth, blotting out the light for an instant, and once she saw a great, stooping shadow limned upon the wall, as if something had paused to peer within the cave. And at the thought of what might rove this land by day Jirel shivered as if in a chill wind, and groped for her crucifix before she remembered that she no longer wore it.

She waited for a long while, clasping cold hands about her knees, watching that blur upon the wall in fascinated anticipation. After a time she may have dozed a little, with the light, unresting sleep of one poised to wake at the tiniest sound or motion. It seemed to her that eternities went by before the light began to pale upon the cave wall.

She watched it fading. It did not move across the wall as sunlight would have done. The blur remained motionless, dimming slowly, losing its tinge of unearthly color, taking on the blueness of evening. Jirel stood up and paced back and forth to limber her stiffened body. But not until that blur had faded so far that no more than the dimmest glimmer of radiance lay upon the stone did she venture out again toward the cave mouth.

Once more she stood upon the hilltop, looking out over a land lighted by strange constellations that sprawled across the sky in pictures whose outlines she could not quite trace, though there was about them a dreadful familiarity. And, looking up upon the spreading patterns in the sky, she realized afresh that this land, whatever it might be, was no underground cavern of whatever vast dimensions. It was open air she breathed, and stars in a celestial void she gazed upon, and however she had come here, she was no longer under the earth.

Below her the dim country spread. And it was not the same landscape she had seen on that other journey. No mighty column of shadowless light swept skyward in the distance. She caught the glimmer of a broad river where no river had flowed before, and the ground here and there was patched and checkered with pale radiance, like luminous fields laid out orderly upon the darkness.

She stepped down the hill delicately, poised for the attack of those tiny, yelping horrors that had raved about her knees once before. They did not come. Surprised, hoping against hope that she was to be spared that nauseating struggle, she went on. The way down was longer than she remembered. Stones turned under her feet, and coarse grass slashed at her knees. She was wondering as she descended where her search was to begin, for in all the dark, shifting land she saw nothing to guide her, and Guillaume’s voice was no more than a fading memory from her dream. She could not even find her way back to the lake where the black god crouched, for the whole landscape was changed unrecognizably.

So when, unmolested, she reached the foot of the hill, she set off at random over the dark earth, running as before with that queer dancing lightness, as if the gravity pull of this place were less than that to which she was accustomed, so that the ground seemed to skim past under her flying feet. It was like a dream, this effortless glide through the darkness, fleet as the wind.

Presently she began to near one of those luminous patches that resembled fields, and saw now that they were indeed a sort of garden. The luminosity rose from myriads of tiny, darting lights planted in even rows, and when she came near enough she saw that the lights were small insects, larger than fireflies, and with luminous wings which they beat vainly upon the air, darting from side to side in a futile effort to be free. For each was attached to its little stem, as if they had sprung living from the soil. Row upon row of them stretched into the dark.

She did not even speculate upon who had sowed such seed here, or toward what strange purpose. Her course led her across a corner of the field, and as she ran she broke several of the stems, releasing the shining prisoners. They buzzed up around her instantly, angrily as bees, and wherever a luminous wing brushed her a hot pain stabbed. She beat them off after a while and ran on, skirting other fields with new wariness.

She crossed a brook that spoke to itself in the dark with a queer, whispering sound so near to speech that she paused for an instant to listen, then thought she had caught a word or two of such dreadful meaning that she ran on again, wondering if it could have been only an illusion.

Then a breeze sprang up and brushed the red hair from her ears, and it seemed to her that she caught the faintest, far wailing. She stopped dead-still, listening, and the breeze stopped too. But she was almost certain she had heard that voice again, and after an instant’s hesitation she turned in the direction from which the breeze had blown.

It led toward the river. The ground grew rougher, and she began to hear water running with a subdued, rushing noise, and presently again the breeze brushed her face. Once more she thought she could hear the dimmest echo of the voice that had cried in her dreams.

When she came to the brink of the water she paused for a moment, looking down to where the river rushed between steep banks. The water had a subtle difference in appearance from water in the rivers she knew—somehow thicker, for all its swift flowing. When she leaned out to look, her face was mirrored monstrously upon the broken surface, in a way that no earthly water would reflect, and as the image fell upon its torrent the water broke there violently, leaping upward and splashing as if some hidden rock had suddenly risen in its bed. There was a hideous eagerness about it, as if the water were ravening for her, rising in long, hungry leaps against the rocky walls to splash noisily and run back into the river. But each leap came higher against the wall, and Jirel started back in something like alarm, a vague unease rising within her at the thought of what might happen if she waited until the striving water reached high enough.

At her withdrawal the tumult lessened instantly, and after a moment or so she knew by the sound that the river had smoothed over its broken place and was flowing on undisturbed. Shivering a little, she went on upstream w

hence the fitful breeze seemed to blow.

Once she stumbled into a patch of utter darkness and fought through in panic fear of walking into the river in her blindness, but she won free of the curious air-pocket without mishap. And once the ground under her skimming feet quaked like jelly, so that she could scarcely keep her balance as she fled on over the unstable section. But ever the little breeze blew and died away and blew again, and she thought the fault echo of a cry was becoming clearer. Almost she caught the far-away sound of “Jirel—” moaning upon the wind, and quickened her pace.

For some while now she had been noticing a growing pallor upon the horizon, and wondering uneasily if night could be so short here, and day already about to dawn. But no—for she remembered that upon that other terrible dawn which she had fled so fast to escape, the pallor had ringed the whole horizon equally, as if day rose in one vast circle clear around the nameless land. Now it was only one spot on the edge of the sky which showed that unpleasant, dawning light. It was faintly tinged with green that strengthened as she watched, and presently above the hills in the distance rose the run of a vast green moon. The stars paled around it. A cloud floated across its face, writhed for an instant as if in some skyey agony, then puffed into a mist and vanished, leaving the green face clear again.

And it was a mottled face across which dim things moved very slowly. Almost it might have had an atmosphere of its own, and dark clouds floating sluggishly; and if that were so it must have been self-luminous, for these slow masses dimmed its surface and it cast little light despite its hugeness. But there was light enough so that in the land through which Jirel ran great shadows took shape upon the ground, writhing and shifting as the moon-clouds obscured and revealed the green surface, and the whole night scene was more baffling and unreal than a dream. And there was something about the green luminance that made her eyes ache.

She waded through shadows as she ran now, monstrous shadows with a hideous dissimilarity to the things that cast them, and no two alike, however identical the bodies which gave them shape. Her own shadow, keeping pace with her along the ground, she did not look at after one shuddering glance. There was something so unnatural about it, and yet—yet it was like her, too, with a dreadful likeness she could not fathom. And more than once she saw great shadows drifting across the ground without any visible thing to cast them—nothing but the queerly shaped blurs moving soundlessly past her and melting into the farther dark. And that was the worst of all.

She ran on upwind, ears straining for a repetition of the far crying, skirting the shadows as well as she could and shuddering whenever a great dark blot drifted noiselessly across her path. The moon rose slowly up the sky, tinting the night with a livid greenness, bringing it dreadfully to life with moving shadows. Sometimes the sluggishly moving darknesses across its face clotted together and obscured the whole great disk, and she ran on a few steps thankfully through the unlighted dark before the moon-clouds parted again and the dead green face looked blankly down once more, the cloud-masses crawling across it like corruption across a corpse’s face.

During one of these darknesses something slashed viciously at her leg, and she heard the grate of teeth on the greave she wore. When the moon unveiled again she saw a long bright scar along the metal, and a drip of phosphorescent venom trickling down. She gathered a handful of grass to wipe it off before it reached her unprotected foot, and the grass withered in her hand when the poison touched it.

All this while the river had been rushing past her and away, and as she ran it began to narrow and diminish; so she knew she must be approaching its head. When the wind blew she was sure now that she heard her own name upon it, in the small wail which had once been Guillaume’s scornful voice. Then the ground began to rise, and down the hillside she mounted, the river fell tinkling, a little thread of water no larger than a brook.

The tinkling was all but articulate now. The river’s rush had been no more than a roaring threat, but the voice of the brook was deliberately clear, a series of small, bright notes like syllables, saying evil things. She tried not to listen, for fear of understanding.

The hill rose steeper, and the brook’s voice sharpened and clarified and sang delicately in its silvery poisonous tones, and above her against the stars she presently began to discern something looming on the very height of the hill, something like a hulking figure motionless as the hill it crowned. She gripped her sword and slackened her pace a little, skirting the dark thing warily. But when she came near enough to make it out in the green moonlight she saw that it was no more than an image crouching there, black as darkness, giving back a dull gleam from its surface where the lividness of the moon struck it. Its shadow moved uneasily upon the ground.

The guiding wind had fallen utterly still now. She stood in a breathless silence before the image, and the stars sprawled their queer patterns across the sky and the sullen moonlight poured down upon her and nothing moved anywhere but those quivering shadows that were never still.

The image had the shape of a black, shambling thing with shallow head sunk between its shoulders and great arms dragging forward on the ground. But something about it, something indefinable and obscene, reminded her of Guillaume. Some aptness of line and angle parodied in the ugly hulk the long, clean lines of Guillaume, the poise of his high head, the scornful tilt of his chin. She could not put a finger on any definite likeness, but it was unmistakably there. And it was all the ugliness of Guillaume—she saw it as she stared. All his cruelty and arrogance and brutish force. The image might have been a picture of Guillaume’s sins, with just enough of his virtues left in to point its dreadfulness.

For an instant she thought she could see behind the black parody, rising from it and irrevocably part of it, a nebulous outline of the Guillaume she had never known, the scornful face twisted in despair, the splendid body writhing futilely away from that obscene thing which was himself—Guillaume’s soul, rooted in the ugliness which the image personified. And she knew his punishment—so just, yet so infinitely unjust.

And what subtle torment the black god’s kiss had wrought upon him! To dwell in the full, frightful realization of his own sins, chained to the actual manifestation, suffering eternally in the obscene shape that was so undeniably himself—his worst and lowest self. It was just, in a way. He had been a harsh and cruel man in life. But the very fact that such punishment was agony to him proved a higher self within his complex soul—something noble and fine which writhed away from the unspeakable thing—himself. So the very fineness of him was a weapon to torture his soul, turned against him even as his sins were turned.

She understood all this in the timeless while she stood there with eyes fixed motionless upon the hulking shape of the image, wringing from it the knowledge of what its ugliness meant. And something in her throat swelled and swelled, and behind her eyelids burnt the sting of tears. Fiercely she fought back the weakness, desperately cast about for some way in which she might undo what she had unwittingly inflicted upon him.

And then all about her something intangible and grim began to form. Some iron presence that manifested itself only by the dark power she felt pressing upon her, stronger and stronger. Something coldly inimical to all things human. The black god’s presence. The black god, come to defend his victim against one who was so alien to all his darkness—one who wept and trembled, and was warm with love and sorrow and desperate with despair.

She felt the inexorable force tightening around her, freezing her tears, turning the warmth and tenderness of her into gray ice, rooting her into a frigid immobility. The air dimmed about her, gray with cold, still with the utter deadness of the black god’s unhuman presence. She had a glimpse of the dark place into which he was drawing her—a moveless, twilight place, deathlessly still. And an immense weight was pressing her down. The ice formed upon her soul, and the awful, iron despair which has no place among human emotions crept slowly through the fibers of her innermost self.

She felt herself turning into some

thing cold and dark and rigid—a black image of herself—a black, hulking image to prison the spark of consciousness that still burned.

Then, as from a long way off in another time and world, came the memory of Guillaume’s arms about her and the scornful press of his mouth over hers. It had not happened to her. It had happened to someone else, someone human and alive, in a far-away place. But the memory of it shot like fire through the rigidness of the body she had almost forgotten was hers, so cold and still it was—the memory of that curious, raging fever which was both hate and love. It broke the ice that bound her, for a moment only, and in that moment she fell to her knees at the dark statue’s feet and burst into shuddering sobs, and the hot tears flowing were like fire to thaw her soul.

Slowly that thawing took place. Slowly the ice melted and the rigidity gave way, and the awful weight of the despair which was no human emotion lifted by degrees. The tears ran hotly between her fingers. But all about her she could feel, as tangibly as a touch, the imminence of the black god, waiting. And she knew her humanity, her weakness and transience, and the eternal, passionless waiting she could never hope to outlast. Her tears must run dry—and then—

She sobbed on, knowing herself in hopeless conflict with the vastness of death and oblivion, a tiny spark of warmth and life fighting vainly against the dark engulfing it; the perishable spark, struggling against inevitable extinction. For the black god was all death and nothingness, and the powers he drew upon were without limit—and all she had to fight him with was the flicker within her called life.

The Complete Jirel of Joiry

The Complete Jirel of Joiry Quest of the Starstone

Quest of the Starstone The Tree of Life

The Tree of Life Judgment Night

Judgment Night The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987

The COMPLEAT Collected SFF Works 1911-1987 Northwest of Earth

Northwest of Earth No Boundaries

No Boundaries The Best of C. L. Moore

The Best of C. L. Moore Doomsday Morning M

Doomsday Morning M Shambleau and Others M

Shambleau and Others M Jirel of Joiry

Jirel of Joiry Judgment Night M

Judgment Night M Northwest Smith

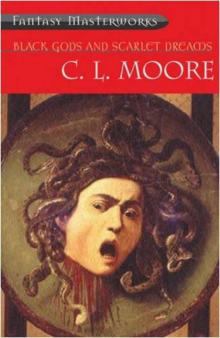

Northwest Smith Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams

Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams